Hugo Boss

Headquarters in Metzingen, Germany | |

| Company type | Public (Aktiengesellschaft) |

|---|---|

| FWB: BOSS MDAX Component | |

| Industry | |

| Founded | 1924 |

| Founder | Hugo Ferdinand Boss |

| Headquarters | , Germany |

Key people | Daniel Grieder (CEO) Yves Müller (CFO/COO) Oliver Timm (CSO)[1] |

| Products | High-fashion Accessories Footwear |

| Revenue | €4.2 billion (2023)[2] |

| €410 million (2023)[2] | |

| €270 million (2023)[2] | |

| Total assets | €3.472 billion (2023)[2] |

| Total equity | €1.311 billion (2023)[2] |

| Owners | Free Float (83%) Marzotto family (15%) Own shares (2%) |

Number of employees | 18,738 (2023)[2] |

| Website | hugoboss |

Hugo Boss AG (stylized as HUGO BOSS) is a luxury fashion company headquartered in Metzingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The company sells clothing, accessories, footwear, and leather goods. Hugo Boss is one of the largest German clothing brands,[3] with global sales of about €4.2 billion in 2023.[2] Its stock is a component of the MDAX.[4] The company's fashion brands are Boss and Hugo. Hugo Boss also sells licensed brand products for children's fashion, eyewear, watches, home textiles, riding apparel, writing utensils and fragrances.[5]

The company was founded in 1924 in Germany by Hugo Ferdinand Boss and originally produced general-purpose clothing. In the early 1930s, Hugo Boss began to produce and supply military uniforms for the Nazi Germany government, resulting in a large boost in sales.[6] After World War II and the founder's death in 1948, Hugo Boss started to turn its focus to men's suits. The company went public in 1988 and introduced a fragrance line that same year, adding men's and women's wear diffusion lines in 1997, a full women's collection in 2000, and children's clothing in 2006–2007. The company has since evolved into a major global fashion house. As of December 2023, it operated 1,418 retail stores worldwide.[2]

History

[edit]Early years

[edit]After the end of the First World War, Hugo Ferdinand Boss (1885–1948) took over his parents' clothing retail business in Metzingen, where it still operates, and registered it as a business for manufactured goods in 1922.[7] In 1924, he started a factory for the production of workwear along with two partners, Albert and Theodor Bräuchle, as shareholders. The company produced shirts, jackets, work clothing, sportswear, and raincoats. In 1925 and 1926, Hugo Boss, like all Metzingen companies, announced Kurzarbeit for its almost 30 employees. In connection with the global economic crisis following the New York stock market crash of 1929, the company had to reduce its workforce by almost a quarter and file for bankruptcy in 1931. In the same year, Hugo Ferdinand Boss reached an agreement with his creditors, leaving him with six sewing machines to start again.[6]

Manufacturing for the Nazi Party

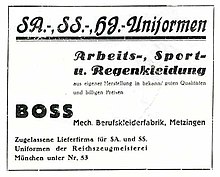

[edit]In 1931, Hugo Ferdinand Boss became a member of the Nazi Party, receiving the membership number 508 889, and a sponsoring member ("Förderndes Mitglied") of the Schutzstaffel (SS).[8] He also joined the German Labour Front in 1936, the Reich Air Protection Association in 1939, and the National Socialist People's Welfare in 1941.[9] He was also a member of the Reichskriegerbund and the Reichsbund for physical exercises.[10] After joining these organizations, he received orders for the production of clothing for the Nazi Party and its organizations, which helped Hugo Ferdinand Boss to stabilize the company again and his sales increased from 38,260 ℛ︁ℳ︁ ($26,993 U.S. dollars in 1932) to over 3,300,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁ in 1941.[6][10] Though he claimed in a 1934–35 advertisement that he had been a "supplier for National Socialist uniforms since 1924", it is probable that he did not begin to supply them until 1928 at the earliest, but was one of the first to produce brown shirts, copies of the "Lettow shirts" introduced to the SA by Gerhard Roßbach in 1924 rather by chance.[10][11] The factory was "one of numerous smaller manufacturing companies involved in uniform production".[6]

Hugo Boss was not involved in the design of the uniform.[12][13] 1924 is also the year the company became a Reichszeugmeisterei-licensed supplier of uniforms to the Sturmabteilung (SA), Schutzstaffel (SS), Wehrmacht, Hitler Youth, National Socialist Motor Corps, and other party organizations.[9][14]

By the third quarter of 1932, the all-black SS uniform was designed by SS members Karl Diebitsch (artist) and Walter Heck (graphic designer). The Hugo Boss company was one of the companies that produced these black uniforms for the SS. By 1938, the firm was focused on producing Wehrmacht uniforms and later also uniforms for the Waffen-SS.[15]

During the Second World War, besides its 300 employees, Hugo Boss employed 140 forced laborers, the majority of them women from the Soviet Union and Poland. In addition to these workers, 40 French prisoners of war also worked for the company briefly between October 1940 – April 1941.[16][17] According to German historian Henning Kober, the company managers were fervent Nazis who were all great admirers of Adolf Hitler. In 1945, Hugo Ferdinand Boss had a photograph in his apartment of him with Hitler, taken at Berghof, Hitler's Obersalzberg retreat.[6][18]

Because of his early Nazi Party membership, his financial support of the SS, and the uniforms delivered to the Nazi party, Hugo Ferdinand Boss was considered both an "activist" and a "supporter and beneficiary of National Socialism".[10][19] In a 1946 judgment, he was stripped of his voting rights, his capacity to run a business, and fined "a very heavy penalty" of 100,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁ ($70,553 U.S.) (£54,008 stg), which was later decreased to 25,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁.[10][19] However, Hugo Ferdinand Boss appealed, and he was eventually classified as a "follower", a lesser category, which meant that he was not regarded as an active promoter of National Socialism.[19]

In June 2000, Hugo Boss joined the Foundation Initiative of German Business for the Compensation of Forced Laborers and contributed financially to the fund.[17] An initial study commissioned by the company at the end of the 1990s on the situation in the Third Reich was not published by the company. The author, Elisabeth Timm, later published it on the internet herself.[10] Later, the economic historian Roman Köster conducted an independent study, which was also financed by the company and published by C. H. Beck in 2011.[6][12] In the same year, the company issued a statement of "profound regret to those who suffered harm or hardship at the factory run by Hugo Boss under National Socialist rule".[20]

Post-war and development into a fashion company

[edit]Hugo Ferdinand Boss died in 1948, but his business survived. His son Siegfried Boss and his son-in-law Eugen Holy took over ownership and management of the company. Production initially focused on uniforms for the French army and the French Red Cross, then on uniforms for the post office, railroads and police.[21] In 1950, the company received its first order for men's suits, resulting in an expansion to 150 employees by the end of the year. Hugo Boss men's suits first appeared on the market in 1953.[22]

By 1960, the company was producing ready-made suits. In 1967, Eugen retired, leaving the company to his sons Jochen and Uwe, who began international development.[23][24] In 1970, the first Boss branded suits were produced and in 1972, the Holy brothers opened the first factory outlet in a nearby warehouse, which later became the Outletcity Metzingen.[25] In 1975, the Austrian designer Werner Baldessarini was hired and eventually became head designer.[26] The Boss brand was registered as a trademark in 1977.[27] This was followed by the start of the company's long association with motorsport, sponsoring Formula One teams.[28]

In 1984, the first Boss branded fragrance appeared. This helped the company gain the required growth for listing on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange the following year.[29] The brand began a golf sponsorship for Bernhard Langer in 1986 and tennis for the Davis Cup in 1987. In 1989, Boss launched its first licensed sunglasses. Later that year, the company was bought by a Japanese group.[30]

After the Marzotto textile group acquired a 77.5% stake for $165,000,000 in 1991,[30][31] the Hugo, Boss and Baldessarini brands were introduced in 1993. In the same year, the Holy-brothers left the company and Peter Littmann became the new Chairman of the Management Board.[32]

In 1995, the company launched its footwear range, the first in a now fully developed leather products range, across all sub-brands. A partnership with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation was launched in 1995, resulting in the Hugo Boss Prize.[33] In 1997, Littmann left the company after differences of opinion with the Marzotto Group and Baldessarini was appointed CEO in 1998.[26]

Women's fashion (Hugo Womenswear) was first introduced in 1998, with the first women's fragrance (Hugo Woman) appearing at the same time.[34][35] Since then, multiple fragrances and skincare ranges have been launched. In January 1999, Hugo Boss launched its first website.[36] Also in 1999, the Boss Orange brand was launched as a separate line for casual wear, followed by Boss Selection (2004) and Boss Green, which emerged from Boss Golf in 2004.[37] 2000 saw the launch of Boss Woman, a product line initially managed by German fashion designer Grit Seymour in Milan,[38] which has since also been presented at Berlin Fashion Week and New York Fashion Week.[39][40][41] In 2002, the company was repositioned with a design team at the Metzingen site.[42][43] The Baldessarini brand was sold to Werner Baldessarini in 2006 and replaced in the Boss range by the Boss Selection collection.[44][45][46] Boss Selection was expanded in 2009 to include Boss Selection Tailored Line, but was integrated into the core Boss brand in mid-2012.[47][48]

Recent history and rise to an international fashion group

[edit]

In 2002, Baldessarini left the company and Bruno Sälzer took over the position of CEO.[49] Under his leadership, Hugo Boss was transformed into a lifestyle group, the women's line was repositioned, and international expansion was driven forward, particularly in the Asian markets.[42][50] In 2005, Marzotto spun off its fashion brands into the Valentino Fashion Group.[51] In 2007, Valentino was acquired by financial investor Permira for €3.5 billion, which subsequently exerted a significant influence on the Hugo Boss company.[52] Sälzer left the company in February 2008.[53] In mid-2008, Permira appointed Claus-Dietrich Lahrs as CEO of Hugo Boss.[54] Shortly afterward, the company launched an online shop in the UK, followed by other countries.[55]

In 2009, the Boss brand was by far the largest segment, consisting of 68% of all sales. The remainder of sales were made up by Boss Orange at 17%, Boss Selection at 3%, Boss Green at 3% and Hugo at 9%.[56] Also in 2009, Hugo Boss was carved out of the Valentino Fashion Group; from then on, the Hugo Boss stake was held by Permira via its Red & Black Holding.[51] Since a share placement on the stock exchange in November 2011, Permira has held around 66% of the total share capital and 89% of the voting rights in Hugo Boss.[57] In 2010, the company had sales of $2,345,850,000 and a net profit of $262,183,000, with royalties of 42% of total net profit.[30] Hugo Boss then had at least 6,102 points of sale in 124 countries. Hugo Boss AG directly owned over 364 shops, 537 mono-brand shops, and over 1,000 franchisee-owned shops.[30]

In June 2013, designer Jason Wu was hired as artistic director of the Boss womenswear collection.[58][59][60][61] The collaboration ended in 2018.[62] In March 2015, Permira announced plans to sell the remaining shares of 12%.[63] Since the exit of Permira, 91% of the shares have been floating on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, and the residual 2% have been held by the company. 15% of the shares are owned by the Marzotto family.[64]

Lahrs left the Group in 2016 and the former CFO Mark Langer was appointed as the new CEO in mid-May.[54] In the same year, Coty took over the perfume licenses for Hugo Boss from Procter & Gamble. A realignment took place shortly afterwards. As a result, the Boss Orange and Boss Green lines were discontinued, and only the Boss and Hugo brands remained active. Furthermore, the company's own global prices were adjusted, while unprofitable stores were closed, existing ones modernized and the e-commerce business was expanded.[65][66] In 2017, Hugo Boss was also included in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index for the first time. In the same year, the sales of Hugo Boss climbed by 7% during the final quarter of the year.[67] In 2020, Mike Ashley's British Frasers Group acquired a stake of around 5% in Hugo Boss.[68] This stake was reduced to 2.63% by February 2023, but Ashley has access to a further 24.69% via financial instruments.[69]

In June 2021, Daniel Grieder took over as CEO of Hugo Boss.[54] Under his direction, the growth strategy Claim 5 was introduced, with the objective of improving the consumer journey and product offerings, increasing relevance, and driving growth across all geographical regions. This strategy is intended to ensure the sustainable growth of the company.[70][71][72]

In the same year, Daniel Grieder set the goal of achieving a revenue of 4 billion euros by 2025.[70] As this revenue target was reached two years earlier, Hugo Boss increased the revenue target for 2025 to 5 billion euros in June 2023.[73]

In 2022, Marco Falcioni was appointed Creative Director.[74] The same year, Hugo Boss invested in the start-up Heiq Aeoniq LLC, which is developing the cellulose fabric Heiq Aeoniq. In 2023, the fiber was first used in the company's textiles.[75]

In order to meet increased demands, the Group invested 100 million euros in a new distribution building at the Bonlanden-Filderstadt site near Stuttgart in the same year. The investments were in digitalization and automation, and robotics applications.[76][77]

In June 2023, Hugo Boss opened the Hugo Boss Digital Campus in Gondomar, Portugal.[78]

Products and business units

[edit]

Since 2017, Hugo Boss has pursued a two-brand strategy, with the core brand Boss (stylized as BOSS) for upscale business and leisure wear and Hugo (stylized as HUGO) for a young target group.[65][80][81] The company has additional licensing agreements with Coty, C.W.F., Movado and Safilo for product collaborations.[82][83][84][85]

Hugo Boss is active in the following segments:

- Boss: The core brand Boss and its sub-brands Boss Black, Boss Orange, Boss Green and Boss Camel offer business clothing and leisurewear ranging from classic to fashionable and casual-sporty.[44][81] The brand offers women's and men's clothing and is aimed at an older target group (millennials).[86][87] In 2022, Boss Womenswear accounted for 10% of the company's total sales.[88]

- Hugo: The Hugo brand began producing fashion for men in 1993, followed by fashion for women (Hugo Womenswear) in 1998.[44][81] The brand is now aimed at Generation Z across all genders.[86][87] In February 2024, Hugo Boss introduced another brand line called Hugo Blue with clothing made from denim and other fabrics.[89][90]

- Children's clothing: Collections for children have been available since 2008, initially under the Boss Orange brand. In 2009, the license for children's clothing was awarded to C.W.F. Children Worldwide Fashion SAS.[91][92] Children's clothing was initially produced exclusively under the Boss brand; since 2022 also under the Hugo brand.[93]

- Shoes: Hugo Boss has been producing shoes since 1995. Initially, MH Shoes & Accessories was a licensee, but since 2004 the Group has been producing the shoes in-house under their Boss and Hugo brands.[94]

- Fragrances: Perfumes, creams, deodorants and shower gels for men and women are offered under the names Boss and Hugo. The first Boss perfume, the men's fragrance Hugo Boss, which was renamed Boss Number One in 1998, is still continued.[5]

- Eyewear and watches: The company has been producing eyewear under license since 1989 and watches since 1996.[95]

- Home textiles: In 2011, the Boss Home collection of bed linen, towelling and other home textiles was also produced under license, presented at a trade fair and subsequently marketed.[96]

- Riding apparel: Since August 2023, Hugo Boss has had riding apparel produced by Bold Equestrian Ltd. under the Boss Equestrian brand.[97]

- Writing instruments: Hugo Boss also has writing instruments manufactured under license.[98]

- Dog accessories: The company has been producing accessories for dogs under license since 2022.[99]

- Tourism industry: early 2024 the company has taken over a luxury rental villa in Balinese Canggu, an area undergoing frenetic tourism development. Their high-paying clients receive Boss-labelled merchandises as freebies.[100]

Products are manufactured in a variety of locations, including the company's own production sites in: Metzingen, Germany; Morrovalle, Italy; Radom, Poland; İzmir, Turkey; and Cleveland, United States.[101]

Hugo Boss has invested in technology for its made-to-measure program, using machines for almost all tailoring traditionally done by hand.[102]

In 2020, Hugo Boss created its first vegan men's suit, using all non-animal materials, dyes, and chemicals.[103]

Shareholders and stock exchange

[edit]The Hugo Boss shares have been included in the MDAX since March 1999.[104] Until June 2012, the share capital was divided into common and preferred stock. On June 15, 2012, after the close of trading, the preference shares were converted into ordinary shares and all shares were converted into registered shares.[105] Since then, the company's share capital has consisted of around 70.4 million no-par value registered ordinary shares.[106] In 2023, a promissory bill loan with a total value of €175 million was placed for the first time.[107]

As at March 2024, the shareholder structure was as follows:[108]

- Free float: 83.00%

- Marzotto family (via PFC S.r.l. / Zignago Holding S.p.A): 15.00%

- Treasury shares: 2.00%

Marketing

[edit]As early as the 1980s, Hugo Boss began with product placements and the outfitting of celebrities. Among other things, Hugo Boss outfitted the actors of the popular US law series L.A. Law and was henceforth seen as the outfitter of yuppies.[109] Hugo Boss dressed the leading actors Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas in the crime series Miami Vice.[22] Other well-known personalities wore Boss outfits at the time, such as Michael Jackson, who wore a white Boss suit on the album cover of Thriller,[110] or Sylvester Stallone, who wore a Boss sweater as Rocky.[111][112]

From 1996 to 2022, Hugo Boss AG sponsored the Hugo Boss Prize, an annual $100,000 stipend in modern arts, awarded by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation every two years as a cultural sponsor, and supported international contemporary exhibitions.[113] In collaboration with the Staatliche Modeschule Stuttgart, the company has presented the Hugo Boss Fashion Award to fashion students since 1987.[114]

In February 2024, a fashion collection designed by supermodel Naomi Campbell was introduced.[115]

Social commitment

[edit]Hugo Boss has been a partner of the child protection organization UNICEF since 2007.[116] In addition, the Group established the Hugo Boss Foundation, whose main source of income is the "Every purchase counts" initiative. Since 2023, 5 cents of every own product (excluding licensed products) have been donated through this initiative. The donations are intended to support local, regional and global impact-oriented projects, particularly in the fields of climate and environmental protection.[117] In 2023, for example, the foundation was involved in the crisis areas affected by earthquakes in Turkey and Syria.[118]

Sustainability

[edit]In 2016, Hugo Boss became a member of the ZDHC Foundation (Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals), which is committed to avoiding harmful substances in production.[119] Since 2017, Hugo Boss has been working on its own contribution to the successful implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.[120] Furthermore, Hugo Boss was part of the Sustainability 2030 science platform initiated by the German government[121] and joined the Klimabündnis Baden-Württemberg in 2024.[122] Sustainability is also part of the Claim 5 strategy implemented by Grieder. As part of this, the resale website Hugo Boss Pre-Loved was launched in 2022, which pursues a circular economy.[123] The investment in the start-up Heiq Aeoniq LLC supports the development of its cellulose fiber Heiq Aeoniq, which is intended to replace chemical fibers such as polyester. Heiq Aeoniq LLC primarily sources its materials from discarded algae, sugarcane, straw, hemp, nutshells, cigarette butts, and coffee grounds.[75][124][125]

At the Hugo Boss Digital Campus, data is processed to make company processes more efficient and to thus improve determination of the demand for products, thereby avoiding the overproduction of clothing. Structures are also being created to better track supply chains. This is in line with the Supply Chain Act, which aims to ensure compliance with environmental and social standards. The company has also announced its intention to become CO2-neutral by 2050.[126]

Since December 2023, Hugo Boss has been the first company to invest in Collateral Good Ventures Fashion I, a climate-related venture capital fund aimed at promoting sustainability in the fashion industry.[127]

Compliance

[edit]The company has introduced structures to ensure compliance. In this context, it works with the Fair Labor Association, has established an ombudsman system, has social audits carried out on working conditions and offers the opportunity to use the Fair Labor Association's comprehensive external and anonymous complaints management system.[128]

Controversies

[edit]Russell Brand

[edit]British comedian and actor Russell Brand was at the 2013 GQ awards, which were sponsored by Hugo Boss. After receiving an award on stage, Brand proceeded to talk about Hugo Boss's Nazi connection and did a goose step. He was later ejected from the ceremony and later apologized.[129]

Wages

[edit]In March 2010, Hugo Boss was boycotted by actor Danny Glover for the company's plans to close the plant in Brooklyn, Ohio, US after 375 employees of the Workers United Union reportedly rejected the Hugo Boss proposal to cut the workers' hourly wage 36% from $13 an hour to $8.30. After an initial statement by CFO Andreas Stockert saying the company had a responsibility to shareholders and would move suit manufacturing from the US to other facilities in Turkey, Bulgaria and Romania,[130] the company capitulated to the boycott and cancelled the project. Renewed plans to close the plant in April 2015 also failed.[131][132]

Mirror fall

[edit]In September 2015, Hugo Boss (UK) was fined £1.2 million in relation to the death in June 2013 of a child who died four days after suffering fatal head injuries at its store in Bicester, Oxfordshire.[133] The four-year-old boy had been injured when a steel-framed fitting-room mirror weighing 120 kilograms (260 lb) fell on him. Oxford Crown Court had earlier been told that it had "negligently been left free-standing without any fixings"[133] and the coroner had said that the death was an "accident waiting to happen".[134] In June 2015, Hugo Boss (UK) had admitted its breach of both the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and Management of Health and Safety at Work regulations 1999.[135] The company's legal representative said:

"The consequence of this failing is as awful as one could reasonably imagine. Since the day of the accident Hugo Boss has done all it can, first to acknowledge those failings, to express genuine, heartfelt remorse and also demonstrate a determination to put things right and ensure there cannot be a repeat of what went wrong."

— Jonathan Laidlaw QC (representing Hugo Boss)[135]

Trademark

[edit]In August 2019, Hugo Boss sent a cease and desist letter, objecting to the trademark application of Boss Brewing, a small brewery based in Swansea,[136] costing the brewery nearly £10,000 in legal fees and compelling them to change the name of several beer brands. Similarly, in November 2023, it was reported that Hugo Boss had sent a cease and desist letter to Canadian fitness company Boss Athletics Inc.[137] In February 2020, professedly as a protest, comedian Joe Lycett changed his legal name to Hugo Boss.[138]

Cotton from Xinjiang

[edit]In 2020, Hugo Boss told NBC News it did not use cotton from the Xinjiang area of China to avoid Uyghur forced labor.[139] However, in 2021, the Chinese subsidiary of Hugo Boss stated on its official Sina Weibo account that they had been using cotton from the region and would continue to do so:[140]

"Xinjiang's long-stapled cotton is one of the best in the world. We believe top quality raw materials will definitely show its value. We will continue to purchase and support Xinjiang cotton."[141]

The statement was later edited to simply saying they have partners "in various regions of China" with a link to an English-language page on their website, which in turn linked to another statement containing the following words: "Hugo Boss has not procured any goods originating in the Xinjiang region from direct suppliers."[142] Initially attracting thousands of likes, the edited Weibo post received many comments accusing the brand of hypocrisy.[143][144] A company spokeswoman stated that the original Weibo post was unauthorized and that the company's position has not changed.[145] According to the company's official statement, all materials are only sourced from suppliers that comply with the Hugo Boss Supplier Code of Conduct.[142]

In September 2021, the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights filed a complaint with German prosecutors accusing Hugo Boss of abetting and profiting from forced labor in Xinjiang.[146] In 2022, researchers from Nordhausen University of Applied Sciences identified cotton from Xinjiang in Hugo Boss shirts.[147]

Sponsorships

[edit]In the field of sports sponsorships, Hugo Boss has been active in motorsport, golf, association football, sailing, tennis, and winter sports.[148][149][150] The company's activities began in the 1970s with the support of racing driver Jochen Mass,[151] and were further expanded in motorsport through the sponsorship of the McLaren Formula 1 team from 1981 to 2014,[152] one of the longest partnerships in motorsport.[28][153] This led to several drivers being outfitted with Hugo Boss clothing, including Alain Prost, Ayrton Senna, and Niki Lauda.[154] Boss has been the official clothing partner of the Aston Martin F1 team since July 2022. One year later, Boss also appointed Aston Martin driver Fernando Alonso as a brand ambassador.[155] In 2024, Boss signed a partnership with David Beckham.[156][157][158]

Athletics

[edit]Players

[edit]Ski

[edit]Races

[edit]Tennis

[edit]Tournaments

[edit] Stuttgart Open (since 2022 Boss Open)

Stuttgart Open (since 2022 Boss Open)

Players

[edit] Matteo Berrettini (global ambassador) (from 2022)

Matteo Berrettini (global ambassador) (from 2022) Taylor Fritz

Taylor Fritz

Formula One

[edit]Teams

[edit] McLaren (1987–2014)

McLaren (1987–2014) Mercedes-Benz (2015–2018)

Mercedes-Benz (2015–2018) Aston Martin (2022–2025)[159]

Aston Martin (2022–2025)[159] RB (2024–)

RB (2024–)

Drivers

[edit]Cycling

[edit]Teams

[edit] Red Bull–Bora–Hansgrohe (2024–)[160]

Red Bull–Bora–Hansgrohe (2024–)[160]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Managing Board)". group.hugoboss.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Hugo Boss Annual Report 2023" (PDF).

- ^ Edwards, Kinga (October 19, 2023). "Fashion ranking: Top 20 clothing retailers in Germany". E-commerce Germany News. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ "MDAX Stocks". Business Insider. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ a b "Hugo Boss: Von Socken bis Parfuems". Wirtschaftswoche (in German). Vol. 51. December 12, 1986. p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f Roman, Köster (2011). Hugo Boss, 1924–1945: Die Geschichte einer Kleiderfabrik zwischen Weimarer Republik und "Drittem Reich" (in German). Germany: C. H. Beck. p. 31. ISBN 978-3406619922.

- ^ Landler, Mark (April 12, 2005). "A Small Town in Germany Fits Hugo Boss Nicely". The New York Times. p. C00001. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Köster, Roman (2011). Hugo Boss, 1924–1945. Die Geschichte einer Kleiderfabrik zwischen Weimarer Republik und „Drittem Reich“. München: C.H. Beck. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-406-61992-2.

- ^ a b "Hugo Ferdinand Boss – Biografie". Who's who. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Timm, Elisabeth (April 12, 2018). "Hugo Ferdinand Boss (1885–1948) und die Firma Hugo Boss" (PDF). Metzingen Zwangsarbeit (in German). Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ^ Höhne, Heinz (1976). Der Orden unter dem Totenkopf: Die Geschichte der SS (in German). Bertelsmann Verlag. ISBN 978-3-570-05019-4.

- ^ a b Obermaier, Frederik (September 23, 2011). "Mode mit brauner Vergangenheit". Süddeutsche (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Köster, Roman (2011). Hugo Boss, 1924–1945. Die Geschichte einer Kleiderfabrik zwischen Weimarer Republik und „Drittem Reich“ (in German). München: C. H. Beck. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-406-61992-2.

- ^ Obermaier, Frederik (September 23, 2011). "Hugo Boss in der NS-Zeit – Mode mit brauner Vergangenheit". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ^ Köster, Roman. "Hugo Boss, 1924–1945. A Clothing Factory During the Weimar Republic and Third Reich" (PDF). Hugo Boss. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2011.

- ^ "Hugo Boss im Dritten Reich: Verstrickt, aber nicht "Hitlers Schneider"". Die Welt (in German). November 22, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Köster Roman, Heise Katrin. "Historiker: Hugo Boss hat nachweislich vom Nationalsozialismus profitiert". Deutschlandfunk Kultur (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Kober, Henning (July 29, 2001). "Über den Umgang mit Zwangsarbeiterinnen bei Boss". Metzinger Zwangsarbeit (in German). Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c Köster, Roman (2011). Hugo Boss, 1924–1945. Die Geschichte einer Kleiderfabrik zwischen Weimarer Republik und „Drittem Reich“. München: C.H. Beck. pp. 96–99. ISBN 978-3-406-61992-2.

- ^ Lipmann, Jennifer (September 22, 2011). "Hugo Boss: 'regret' for Holocaust record". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Köster, Roman (2011). Hugo Boss, 1924–1945. Die Geschichte einer Kleiderfabrik zwischen Weimarer Republik und „Drittem Reich“. München: C.H. Beck. p. 101. ISBN 978-3-406-61992-2.

- ^ a b "Hugo Boss". Brandslex. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Alexander, Charles P.; Mondi, Lawrence; Wolf, Uwe (October 9, 1984). "A Boss Look for the Boardroom". Times Magazine. Vol. 11.

- ^ "Mekka Metzingen". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Vol. 11/2019. March 14, 2019.

- ^ Bogen, Uwe (October 21, 2022). "50 Jahre Outlet City Metzingen: „La Dolce Vita" bei Promi-Party in harter Zeit". Stuttgarter Nachrichten (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Angelopoulou, Alexia (August 26, 2006). "Stilsicherer Überzeugungstäter". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Vol. 198. p. 14.

- ^ "Hugo Boss Group: Geschichte". Hugo Boss Group. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Zengler, André (May 18, 2010). "McLaren und Hugo Boss gehen ins 30. Jahr". Speedweek (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Rathenow, Solveig (March 11, 2021). "Sportkleidung statt Anzug: Die angeschlagene Modemarke Hugo Boss macht Verluste in Millionenhöhe". Business Insider (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Chevalier, Michel (2012). Luxury Brand Management. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118171769.

- ^ "Marzotto S.p.A." The New York Times. November 2, 1991. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ Dorfs, Joachim (March 1, 1993). "„Ab heute herrscht Wettbewerb zu den Holys" – Gespräch mit Vorstandschef Dr. Peter Littmann. Die Trennung des Herrenmodeherstellers von den Brüdern wird komplett vollzogen". Handelsblatt (in German).

- ^ "Timeline of the Hugo Boss Prize". Guggenheim. December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ "Hugo soll jetzt damenhaft den Markt erobern". Handelsblatt (in German). Vol. 22. February 2, 1998. p. 17.

- ^ "Boss: Hugo für die Damen". Textilwirtschaft (in German). April 10, 1997.

- ^ "Hugo Boss ist online". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Vol. 4. January 28, 1999. p. 290.

- ^ Schreier, Gabi (June 12, 2008). "Selbst gestrickte Werbung: Der Modekonzern Hugo Boss nimmt die Markenführung selbst in die Hand". Werben & Verkaufen (in German). Vol. 24. p. 24.

- ^ "Hugo Boss AG". International Directory of Company Histories. Vol. 128. Detroit: St. James Press. 2012. pp. 264–269.

- ^ Werner, Michael (July 17, 2007). "Big Bang in Berlin". Textilwirtschaft (in German).

- ^ Kusserow, Alexandra (February 13, 2014). "Jason Wow!". Stylebook.

- ^ Dingwall, Kate (November 21, 2016). "Hugo Boss opts out of New York Fashion Week". Fashion Network.

- ^ a b Borghardt, Liane; Bilen, Stefanie; Mönnighoff, Patrick (March 1, 2006). "Ware Schönheit. Beauty Business Nicht nur schön". Junge Karriere (in German). p. 16.

- ^ Schipp, Anke (February 7, 2005). "Modezaren: Vom Verschwinden der Stardesigner". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Boss setzt auf Drei. Hugo, die Modische, Boss, die Klassische, und Baldessarini, die Edle, sind die drei neuen Marken, die die Hugo Boss AG unter der Dachmarke Hugo Boss ab 1994 ins Markt-Rennen schickt". Werben & Verkaufen (in German). August 20, 1993.

- ^ "ABC eines Preisträgers". Absatzwirtschaft (in German). Vol. (Sonderausgabe Marketing für die Zukunft). October 10, 2006.

- ^ Polte, Peter Paul (April 8, 2004). "Boss Woman ist aus dem Schneider". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Vol. 15. p. 6.

- ^ Probe, Anja (March 10, 2009). "Unternehmen: Boss Selection bringt Tailored Line auf den Markt". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Modekonzern strafft Markenstruktur und stärkt seine Kernmarke". Berliner Morgenpost (in German). July 12, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Personalie: Stabwechsel bei Boss". Börsen-Zeitung. Vol. 101. May 29, 2002. p. 13.

- ^ "Steine auf dem Weg in die Weltliga". Südwest Presse (in German). August 1, 2008. p. 3.

- ^ a b "Marzotto wird wieder Boss-Großaktionär". Börsen-Zeitung (in German). Vol. 28. February 11, 2015. p. 9.

- ^ Noé, Martin (November 2, 2009). "Boss in Not". Manager Magazin (in German).

- ^ Hesse, Martin (May 11, 2010). "Permira boxt Dividende durch". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German).

- ^ a b c Dunzendorfer, Martin (March 30, 2023). "In Hugo Boss sind Erfolge eingepreist". Börsen-Zeitung (in German).

- ^ "Hugo Boss richtet Online Store ein". Reutlinger General Anzeiger (in German). September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Results of Operations in Fiscal Year 2009". Hugo Boss AG. Archived from the original on September 2, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "Finanzinvestor: Permira verkauft Boss-Aktien". Stuttgarter Zeitung (in German). November 14, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Hugo Boss baut mehr Läden für Asiaten". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Vol. 276. November 27, 2013. p. 13.

- ^ "Jason Wu wird Artistic Director für Boss Womenswear". Vogue. June 10, 2013. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Hugo Boss' Jason Wu breaks the rules and goes from success to success". Australian Financial Review. June 29, 2016. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Whitney, Christine (May 20, 2015). "How Jason Wu Became Hugo Boss's New Leading Man". Harper's Bazaar. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Nowicki, Jorg (December 20, 2018). "Die Köpfe des Jahres". Textilwirtschaft (in German). pp. 38–40.

- ^ "Finanzinvestor: Permira steigt bei Hugo Boss aus". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). March 16, 2015. ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Mehr Anteile an Hugo Boss". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). February 16, 2020. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Brück, Mario (November 16, 2016). "Hugo Boss: Boss-Anzüge werden in Deutschland teurer". Wirtschaftswoche (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Hugo Boss stattet jetzt die Formel E aus: Was steckt dahinter?". Die Welt (in German). March 18, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Felstedt, Andrea (January 16, 2018). "The Boss Is Back". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Hughes, Huw (June 15, 2020). "Britischer Einzelhändler Frasers Group steigt bei Hugo Boss ein". FashionUnited (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Release according to Article 40, Section 1 of the WpHG [the German Securities Trading Act] with the objective of Europe-wide distribution". EQS News. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Shearsmith, Tom (August 4, 2021). "Hugo Boss presents new growth strategy to double sales to €4 billion by 2025". The Industry Fashion. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Scherbaum, Christoph (March 17, 2023). "Hugo Boss: Schwäbische Eleganz". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Modehändler mit Wachstum: Hugo Boss spürt wenig von der Konsumzurückhaltung". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). August 2, 2023. ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Bayer, Tobias (June 15, 2023). "Kapitalmarkttag: Hugo Boss hebt Umsatzziel auf 5 Mrd. Euro an". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Gräfe, Daniel (October 25, 2023). "Kreativchef Marco Falcioni: Der Mann, der Hugo Boss wieder hip machte". Stuttgarter Zeitung (in German). Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Gropler, Melanie. "Nach der 5 Millionen-Investition: Boss weitet Einsatz von nachhaltigerem Gewebe auf Mode aus". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Dörpmund, Tim (October 26, 2023). "Ausbau des Logistikzentrums: Hugo Boss investiert 100 Mio. Euro in Filderstadt". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Gräfe, Daniel (October 26, 2023). "Ausbau des Logistikzentrums: Hugo Boss will in Filderstadt bis zu 300 Jobs schaffen". Stuttgarter Nachrichten (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Knieps, Stephan (June 15, 2023). "Hugo Boss mit Rekordzahlen: Der Trick hinter Hugo Boss' neuem Höhenflug". Wirtschaftswoche (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Boss Bottled (1998)". Basenotes. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ Weishaupt, Gerog (November 2, 2017). "Modebranche: Hugo Boss setzt auf eigene Läden". Handelsblatt (in German).

- ^ a b c Knieps, Stephan (November 7, 2022). "Wie Daniel Grieder bei Hugo Boss die Wende schafft". Wirtschaftswoche (in German).

- ^ "Safilo Group S.p.A/". Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ "Movado Group Inc". Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ Schroder, Jan (December 20, 2022). "Hugo Boss und Coty verlängern Parfüm-Lizenzpartnerschaft". FashionUnited (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Schroder, Jan (July 19, 2022). "Hugo Boss: CWF erhält Kindermode-Lizenz für die Marke Hugo". FashionUnited (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Knieps, Stephan (April 21, 2023). "Hugo-Boss-Chef Daniel Grieder: „Mit unserem Anzug kann man sogar Rad fahren"". Wirtschaftswoche (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Schmale, Oliver (August 26, 2023). "Daniel Grieder krempelt Hugo Boss um". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Geschäftsbericht 2022" (PDF). Hugo Boss Group. 2022.

- ^ Burney, Chloe (May 9, 2023). "Hugo Boss launches denim sub-brand Hugo Blue". The Industry Fashion. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Palmieri, Jean E. (May 8, 2023). "Hugo Boss to Launch Denim-skewed Collection Called Hugo Blue". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ "In Kürze – Hugo Boss". Textilwirtschaft (in German). December 6, 2007.

- ^ Metzner, Martina (July 23, 2009). "Cleane Couture für den kleinen Boss". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Vol. 30. p. 61.

- ^ Dörpmund, Tim (January 7, 2022). "Hugo Boss erweitert Lizenzabkommen für Kindermode". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Hugo Boss fertigt Schuhe und Leder zukünftig selbst". Horizont (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Hake, Bernd; Hüsgen, Kathrin (2013). Riekhof, Hans-Christian (ed.). Changing the Model − Hugo Boss wandelt sich vom statischen Wholesale-Unternehmen zum dynamischen Retailer (in German) (3 ed.). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. p. 358. ISBN 978-3-8349-4554-9.

- ^ "Kuscheln mit Hugo und Bruno". Handelsjournal (in German). Vol. 10/2011.

- ^ Spötter, Ole (August 31, 2023). "Hugo Boss schwingt sich in den Sattel und startet Reitbekleidungslinie". FashionUnited (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Hugo Boss Geschäftsbericht 2015".

- ^ "Hugo Boss ist auf den Hund gekommen". Reutlinger General Anzeiger (in German). May 19, 2022.

- ^ "Big Name Brands Announce Hotel And Villa Projects In Bali". thebalisun.com. May 27, 2024. Retrieved June 5, 2024.

- ^ "Hugo Boss AG Organisational Structure". Hugo Boss AG. Archived from the original on March 23, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ Binnberg, Nils (April 11, 2017). "Techno tailor: Boss is revolutionising the made-to-measure suit". Wallpaper.

- ^ Oberschür, Rüdiger (March 16, 2020). "Hugo Boss launches vegan suit". Fashion Network. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ "FAQ Investor Relations". Hugo Boss Group. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Lusebrink, Lars (July 9, 2012). "Analysten-Kommentar zu Hugo Boss". Textilwirtschaft (in German).

- ^ "Aktie". Hugo Boss Group. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Dörpmund, Tim (October 25, 2023). "Premiere für den Modekonzern: Hugo Boss: 175 Mio. Euro via Schuldscheindarlehen". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Aktionärsstruktur". Hugo Boss Group. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Clark, Andrew (February 24, 2001). "Dressed for success". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Sack, Adriano (September 2, 2018). "Der weiße Anzug". Welt am Sonntag (in German). Vol. 35. p. 61.

- ^ Meier, Ernst (June 10, 2015). "Die Stadt Zug steht Hugo Boss gut". Neue Zuger Zeitung (in German). p. 45.

- ^ Emig, Silke; Bayer, Tobias (September 20, 2021). "„Da passen wir wahnsinnig auf"". Textilwirtschaft (in German). pp. 50–51.

- ^ Durón, Maximilíano (September 23, 2022). "Guggenheim Museum Nixes Closely Watched $100,000 Hugo Boss Prize". ARTnews. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Eberhardt, Daniela (March 13, 2010). "Die schwarze Krawatte hat Kleckse in Kupferrot Schauplatz Stuttgart". Stuttgarter Zeitung (in German). p. 22.

- ^ Donnell, Chloe Mac (February 14, 2024). "Naomi Campbell creates clean-cut Boss range with nod to her germophobia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Luft, Oliver (September 2, 2011). "Sienna Miller and Orlando Bloom star in Hugo Boss African schools campaign". Campaign Live. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Halliday, Sandra (December 15, 2022). "Hugo Boss launches eco-supporting foundation, percentage of all sales to be donated". Fashion Network. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Nowicki, Jörg. "Von Adidas bis Zara: So hilft die Branche in der Erdbeben-Region". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Hackenberg, Andrea (April 27, 2017). "Unternehmen: Öko-Stiftung ZDHC: Hugo Boss wird Mitglied". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Styles, David (April 30, 2018). "Hugo Boss outlines UN SDG contribution targets". Ecotextile News. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Ronzheimer, Manfred (May 12, 2017). "Lösungsbeschleuniger für die Weltprobleme". Die Tageszeitung (in German). p. 18.

- ^ "Hugo Boss: Beitritt zum Klimabündnis". Metzinger Uracher Volksblatt. 2024-02-03 (in German), p. 13.

- ^ Rogowski, Uwe (April 22, 2022). "Hugo Boss plant Resale-Plattform". Reutlinger General Anzeiger (in German).

- ^ Reinhold, Kirsten (October 13, 2022). "Fokus Greenwashing: Das Polyester-Problem". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Roberts-Islam, Brooke (July 5, 2023). "MAS Holdings And HeiQ Take Sustainable 'plant polyester' Mass Market". Forbes. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Mix, Ulrike (September 2, 2023). "Deshalb läuft es so gut beim Modekonzern Hugo Boss aus Metzingen". Swr (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Sillitoe, Ben (December 7, 2023). "Collateral Good: Hugo Boss backs venture capital fund dedicated to sustainable fashion". Green Retail World. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Isabel (2018). Jastram, Sarah Margaretha; Schneider, Anna-Maria (eds.). Sustainability Strategies in Luxury Fashion: Company Disclosure on Human Rights. Sustainable Fashion. Governance and New Management Approaches (1 ed.). Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 978-3-319-74366-0.

- ^ Hyde, Marina (September 5, 2013). "GQ award-winner Charles Moore cracks Russell Brand's 'Nazi' comment". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Glover calls for Hugo Boss boycott at the Oscars". NBC News. March 7, 2010. Retrieved December 1, 2023.

- ^ Perkins, Olivera (December 2, 2014). "Hugo Boss says it will close Cleveland area plant in 2015, but unions ready to fight it — again". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Perkins, Olivera (March 20, 2015). "Hugo Boss plant will stay open with new owners, saving 160+ jobs". The Plain Dealer.

- ^ a b "Hugo Boss fined £1.2m over Bicester Village mirror death". BBC News Online. September 4, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ "Bicester Hugo Boss store admits charges over boy's mirror death". BBC News Online. June 3, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "Hugo Boss faces huge fine over toddler's death in store". The Guardian. September 3, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ "Welsh brewery spends nearly £10,000 in battle with clothing giant over name". ITV News. August 12, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ "Who's the Boss? Sask. cheer company runs afoul of Hugo Boss over its name". CBC News. November 3, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "Joe Lycett: Comedian changes his name to Hugo Boss". BBC News. March 2, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ Nadi, Aliza; Schecter, Anna; Martinez, Didi (September 22, 2020). "Is the cotton in your shirt from Chinese forced labor?". NBC News. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ "Hugo Boss, Asics will continue buying Xinjiang cotton". La Prensa Latina Media. March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ Grundy, Tom. "Hugo Boss tells Chinese customers it will continue to purchase Xinjiang cotton, whilst own website says it has never used it - Hong Kong Free Press HKFP". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ a b "Hugo Boss Statement on the Chinese region of Xinjiang" (PDF). Hugo Boss Group.

- ^ "Sina Visitor System". Passport Weibo.

- ^ Lew, Linda (March 26, 2021). "Hugo Boss' Xinjiang comments spark accusations of hypocrisy online". South China Morning Post. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ "Und Hugo Boss laviert herum ..." Zeit online (in German). March 30, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ "Rights group files complaint against German retailers over Chinese textiles". Reuters. September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ Oltermann, Philip (May 5, 2022). "Xinjiang cotton found in Adidas, Puma and Hugo Boss tops, researchers say". The Guardian. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ "Sportsponsoring". Hugo Boss Group. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Freutel, Aziza (May 1, 2008). "Fußball in Mode". Textilwirtschaft (in German).

- ^ "Vendée Globe: Und wenn Segelprofi Alex Thomson auf See stirbt?". Die Welt (in German). February 19, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Holmes, Elena (November 10, 2017). "Report: Hugo Boss to move from Formula One to Formula E". SportsPro. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ "Hugo Boss to leave McLaren for Mercedes". Times of Malta. July 7, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Cooper, Adam (July 6, 2014). "McLaren und Hugo Boss: Aus nach 33 Jahren!". Speedweek (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Teo, Annabelle (May 30, 2011). "Dress a Formula One Driver with Hugo Boss and McLaren". Tatler Asia. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Stephens, Cassidy (July 24, 2023). "Boss names Fernando Alonso brand ambassador with sports clearly key for label". Fashion Network. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ "David Beckham va imaginer des collections de mode homme pour Hugo Boss". GQ France. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ "Hugo Boss signe une collaboration à long terme avec David Beckham". Journal du Luxe. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ "Hugo Boss s'associe à David Beckham". Fashion Network. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Bayer, Tobias (July 24, 2023). "Sportsponsoring: Boss bindet Fernando Alonso an sich". Textilwirtschaft (in German). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ @redbullborahansgrohe. "Please welcome @boss". www.instagram.com. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

External links

[edit]- 1980s initial public offerings

- Clothing brands of Germany

- Clothing companies established in 1924

- Companies based in Baden-Württemberg

- Companies in the MDAX

- Companies listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange

- Eyewear brands of Germany

- German companies established in 1924

- Germany home front during World War II

- High fashion brands

- Perfume houses

- Sportswear brands

- Suit makers

- Underwear brands

- Valentino Fashion Group

- Permira companies

- Liam Payne